Experts sound the alarm: Starlink satellites could cause irreversible damage by 2035

Experts are sounding louder alarms about mega constellations clogging low Earth orbit. On WION’s podcast, researchers and former regulators warn that by 2035 we could tip into irreversible harm if the pace of launches, failures, and reentries continues unchecked.

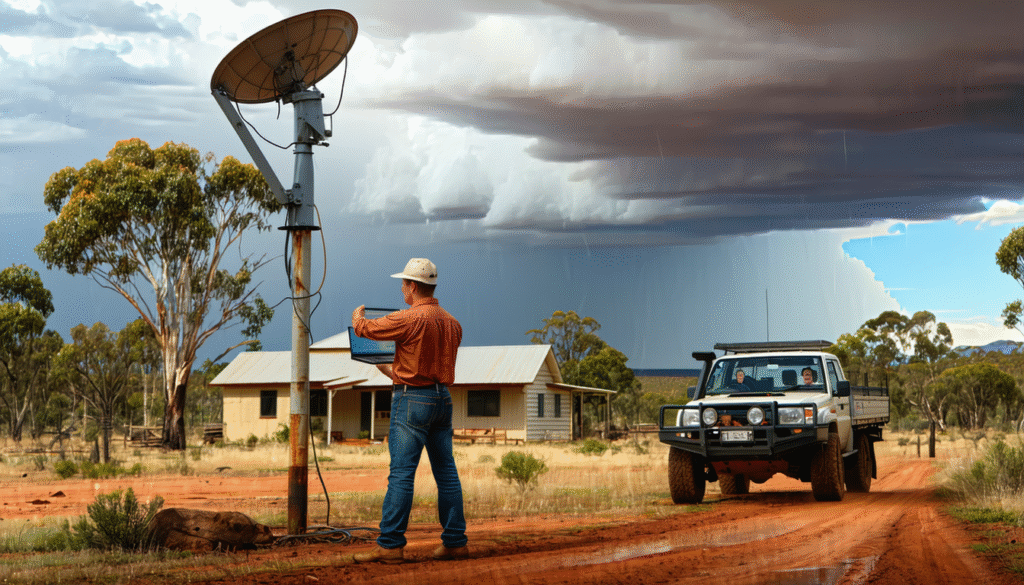

The fear is not Hollywood-style collisions, but a slow grind: dozens of satellites reentering each week, aluminum compounds building up in the upper atmosphere, radio noise swamping faint signals from the cosmos, and a growing chance of cascading debris. If you rely on Starlink for work, school, or safety, you probably feel torn. It helps real people every day. I’ve seen it change lives in rural Australia and on off-grid farms. Still, the costs to the sky are adding up, and that tension is why this story matters.

This piece breaks down the reentry problem, the science of radio interference, what it means for users on the ground, how Starlink stacks up against OneWeb, Amazon Kuiper, Viasat, HughesNet, SES, Telesat, and Iridium, and the policy levers that could keep space usable. I bring data, quotes, and my own field notes from dead zones where people cheered when a dish came online. If you want straight answers with real context, you’re in the right place. Let’s look at what is changing fast, what’s still in our control, and what you can do right now to help protect the sky you depend on.

In brief

- Reentries are rising – analysts say one to two Starlink satellites now burn up daily, with more to come as constellations grow.

- Astronomy is hurting – bright streaks and radio noise are reshaping research plans and telescope schedules.

- Users benefit today – rural families get real broadband, but reliability can wobble during upgrades and storms.

- Alternatives exist – OneWeb, Amazon Kuiper, Viasat, HughesNet, Telesat, SES, and Iridium each have trade-offs.

- 2035 is a line in the sand – better rules, cleaner hardware, and smarter operations can keep space safe if we act.

Starlink satellites are reentering daily: what experts fear could be irreversible by 2035

Here is the blunt part first: multiple trackers report that one to two Starlink satellites reenter Earth’s atmosphere every day. That is not rumor. It’s been tallied by independent analysts and covered in mainstream tech outlets. You can read the short version in pieces like this PCWorld report and Popular Mechanics’ summary. The pattern tracks with higher failure rates for early batches, solar storms trimming orbital lifetimes, and routine end-of-life disposals. On any given week, you may see dozens of reentries if you follow the logs.

Why does that matter? Each satellite is mostly aluminum. When they burn up, they create fine aluminum oxides that drift in the upper atmosphere. Scientists are still nailing down the totals, but early modeling suggests significant deposition as constellations scale. That could affect ozone chemistry and stratospheric heating. The evidence is not settled, yet the risk is plausible enough that several labs have shifted attention to it. For a wider view on today’s pace and tomorrow’s implications, see Fast Company’s explainer and this roundup on Daily Galaxy.

The other fear is a cascade. You might know the term Kessler syndrome from sci-fi, but real engineers treat it as a math problem. If failure rates, traffic density, and collision cross sections pass certain thresholds, junk multiplies faster than it decays. Starlink’s operators at SpaceX say they design for controlled deorbit, fast decay, and improved fault handling. True, and the record shows many safe disposals. But in a crowded sky, Murphy’s law gets a vote.

Are burning satellites polluting the upper atmosphere?

Short answer: probably some, and the trend is rising. The detail that spooks atmospheric chemists is the potential for alumina particles to interact with ozone cycles at high altitude. I have heard radio astronomers and climate researchers use careful language about this. They do not claim catastrophe, but they do call for caps and impact accounting. One bright spot is next-gen hardware: Starlink V3 is pitched as more efficient and resilient. Coverage like this V3 preview hints at bigger capacity per satellite, which could mean fewer units for the same throughput if operators choose that path.

- Risk bucket 1 – daily reentries adding alumina to the stratosphere.

- Risk bucket 2 – debris generation from failures and close calls.

- Risk bucket 3 – spectrum congestion and radio interference.

| Year | Estimated active Starlink units | Daily reentries range | Key unknowns | Potential mitigation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2024 | ~6,000 – 7,000 | 1 – 2 | Alumina totals, storm impacts | Faster deorbit commands, better shielding |

| 2027 | Higher by several thousand | 2 – 4 | Combined effect with other constellations | Shared debris-removal services |

| 2030 | Large-scale replenishment cycles | 3 – 6 | Ozone chemistry response | Capped reentry mass per day |

| 2035 | Plateau or expand based on policy | 4 – 8+ | Runaway congestion risk | Strict end-of-life rules and audits |

One final note for this section: alarm bells are there to start a fix, not to blame users who rely on the service. The key insight is simple: scale without guardrails becomes self-defeating, and 2035 is a sensible target to get those guardrails in place.

Radio interference and astronomy: how megaconstellations reshape the sky for science

Ask any radio astronomer about the last three years and you will hear the same sigh. Sensitive bands that used to be quiet now have more spurious emissions and out-of-band noise. Reports like this overview from RFI show how observations get scrambled. An even sharper example came when investigative journalists traced military satellites to emissions on frequencies reserved for Earth stations, which the Numerama article flagged as contrary to norms. The message to policy folks is clear: keeping space useful means respecting both licenses and the spirit of coordination.

Optical astronomy has its own headache. When you plan a night on a 4-meter telescope and half your long exposures catch bright streaks, your data is toast. SpaceX has tried darker coatings and different orientations to cut reflectivity. Those tweaks help a little, but they do not erase the problem. Add in ground-to-satellite links hopping among beams, and radio telescopes can feel like they are trying to listen to a whisper next to a concert speaker.

Why do scientists say the interference is already disruptive?

Because they are losing time. That is the most precious resource in this field. Observing windows are finite, proposal cycles are competitive, and weather is a coin toss. I sat with a graduate student in a control room who watched a rare target drift behind a streak and simply said, “There goes my month.” Multiply that across dozens of projects and the hidden cost is huge.

- Optical impact – more streaks, more masking, lost exposures.

- Radio impact – out-of-band leakage, side lobes, unplanned beaming.

- Mitigation needs – stronger coordination, live beam-shaping, quiet zones.

| Interference type | What it looks like | Primary victims | Current responses | What would help |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Optical streaks | Bright trails across long exposures | Survey telescopes, transient hunters | Masking, scheduling around passes | Lower reflectivity, fewer units per shell |

| Out-of-band emissions | Raised noise floor near protected bands | Radio astronomy arrays | Filters, coordination requests | Hardware limits and better enforcement |

| Beam spillover | Side lobes hitting quiet zones | Remote observatories | Notices to operators | Automated geofenced beam shaping |

If you want the human side, CNET’s feature on the rise of 7,000 Starlink satellites captures both the promise for users and the growing frustration in labs. The bottom line here is not anti-innovation. It is pro-science and pro-quiet-sky. We need signals from the universe more than we need streaks in our photos, and that asks for smarter design and rules across all operators.

What falling satellites mean for everyday users: reliability, weather, and real fixes

Let’s talk about life on the ground. I’ve installed dishes on tin roofs and seen kids high-five when video class finally worked. In Western Australia, early adopters swapped patchy 4G for Starlink and never looked back. Real-world performance depends on your sky view, your cabling, and the network’s current load. If your dish drops out during a storm, you’re not imagining it. See this practical breakdown on how weather affects Starlink speeds, which matches what I’ve seen during squalls.

Upgrades can be a double-edged sword. When SpaceX races to add capacity, there can be short-term instability as new units mesh into the network. The V3 generation promises higher throughput per bird, and that could reduce the total number needed per region. If you want a grounded take on that, this primer on the Starlink V3 shift pairs well with the French preview of faster V3 satellites.

What should you do if your Starlink dish keeps dropping out?

Start simple. Reboot the router and dish, then check obstruction maps. Swap suspect cables. If that fails, this guide to five common Starlink setup issues is the checklist I send to friends. For rural installs, a mast can change everything. An experienced tech will clear tree lines and avoid metal interference. If you’re in Australia, here’s a clear walk-through on satellite dish installation.

- Fast fixes – power cycle, clear obstructions, reseat connectors.

- Site upgrades – raise the mount, use proper grounding, weatherproof joins.

- Network factors – temporary drops during satellite handoffs or storms.

| Location | Typical down speed | Typical up speed | Common bottleneck | What helps |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Perth metro | 150 – 250 Mbps | 15 – 25 Mbps | Peak-time congestion | Router QoS, off-peak downloads |

| WA regional | 80 – 180 Mbps | 10 – 20 Mbps | Obstructions, weather bursts | Higher mast, cable swaps |

| Remote outback | 50 – 120 Mbps | 5 – 15 Mbps | Thermal throttling, dish icing | Shade in heat, heater in cold |

If you want a local snapshot, these notes on Starlink speeds in Perth and WA match what my neighbors report. For a broader view on access, take a look at how remote Australia got online. Solid service will matter even more if reentry rates climb, because you need fewer satellites if each one carries more load reliably. That’s the quiet lever users forget: better capacity per unit is cleaner for the sky.

Growth is not slowing. You can skim launch cadence updates like this note on Falcon 9 boosting the network or this rundown of a fresh batch of satellites. Expansion helps rural schools and clinics today. The question is how to keep that help without the hidden bill arriving in 2035.

Starlink vs OneWeb, Amazon Kuiper, Viasat, HughesNet, Telesat, SES, and Iridium: who keeps the sky safest?

People ask me if switching providers solves the space-risk problem. The honest answer: it depends. Starlink runs the largest low Earth orbit network today. OneWeb is smaller and targets enterprise and carrier backhaul. Amazon Kuiper is entering with heavy funding and plans to ride rockets from partners including Blue Origin. Viasat and HughesNet use high-altitude geostationary or medium orbits, so they add less clutter to low Earth orbit but can feel slower on latency. Telesat has a LEO plan with focus on enterprise links. SES runs both GEO and MEO fleets, pairing them with smart ground gear. Iridium runs a lean LEO network focused on voice and IoT, with smaller satellites and tight procedures.

Safety is a mix of altitude, density, deorbit discipline, and spectrum hygiene. Even a careful operator can cause headaches at scale. Conversely, a smaller constellation with solid end-of-life rules can be a better neighbor. If you want market context for growth pressure, here’s a sober CNET read on the inevitable downsides of 7,000 satellites and a business angle on competition as Amazon challenges Starlink in Europe.

- Low orbit players – Starlink, OneWeb, Telesat, Iridium, Amazon Kuiper.

- Higher orbit players – SES, Viasat, HughesNet with GEO and MEO focus.

- Key safety levers – fewer units per coverage area, faster deorbit, cleaner beams.

| Operator | Typical orbit | Network scale | Latency feel | Potential sky-risk profile |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Starlink | LEO shells | Very large | Low | High density – needs strict deorbit discipline |

| OneWeb | LEO | Smaller | Low | Moderate – fewer satellites reduce crowding |

| Amazon Kuiper | LEO | Planned large | Low | To be proven – depends on Blue Origin launch cadence and ops choices |

| Viasat | GEO/MEO | Small number of big birds | Higher | Lower LEO clutter but GEO debris risks differ |

| HughesNet | GEO | Small | Higher | Minimal LEO footprint |

| Telesat | LEO planned | Targeted | Low | Depends on ops rules and end-of-life plan |

| SES | GEO/MEO mix | Moderate | Medium | Lower LEO impact, spectrum care still needed |

| Iridium | LEO | Lean | Low | Low density with strict procedures |

For raw reentry context, the cadence stories from Fast Company and this Daily Galaxy note frame how growth changes risk math. If Kuiper scales quickly, Starlink tightens shells, and OneWeb refreshes hardware, LEO could feel like a rush-hour freeway. The safer version of that future is possible if each player prioritizes fewer, smarter, cleaner satellites.

One more angle: policy and geopolitics. A piece in Forbes France lays out what a fresh space race could mean for communications in conflict, including Starlink’s role in Ukraine. It’s a sober read on dual-use realities and why rules matter in tense times. If that context helps, here is the analysis on a new star war.

Policy, safeguards, and user choices to avoid irreversible harm by 2035

I keep a simple mental model for safer space: fewer units, cleaner beams, faster goodbye. Regulators can set the floor, but operators and users shape behavior daily. Practical changes include capping daily reentry mass, requiring on-board features that guarantee disposal within a short window after failure, and auditing spectrum behavior in the wild, not just in lab tests.

We have seen signs that governance can move. One headline that stuck with me involved SpaceX remotely shutting down thousands of receivers used by cyberfraud rings in Myanmar. That kind of control, covered here by TVA Nouvelles, shows that networks can enforce rules when pushed. Different issue, same point: operators can act decisively when risk is high.

Policy does not happen in a vacuum. National politics and spectrum auctions shape who gets to operate and how. This summary on service expansion facing political hurdles is a useful snapshot from ground level. Meanwhile, industry coverage continues to track where satellites are failing and falling. You can cross-check with this overview of increased reentries and the tech press noting that satellites are falling from the sky.

- Regulatory moves – cap daily reentry totals, require proof of disposal, publish independent audits.

- Operator moves – scale with V3 efficiency, geofence beams, share live tracking data with observatories.

- User moves – site dishes cleanly, update firmware, back public funding for debris removal.

| Mitigation lever | Who acts | Near-term impact | Long-term benefit | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Reentry mass cap per day | Regulators | Immediate ceiling | Limits alumina buildup | Scaled to total constellations, not one brand |

| Audited end-of-life plans | Operators | Cleaner disposals | Lower debris totals | Spot checks using independent trackers |

| Spectrum hygiene watchdog | Industry and ITU members | Fewer radio conflicts | Protects telescopes | Responds to cases like those in Numerama and RFI |

| Fewer, more capable satellites | Operators | Less traffic | Lower collision risk | Leans on V3-class hardware gains |

| Debris-removal funding | Governments | Pilot projects | Insurance for 2035 | Public-private model fits here |

People often ask me what a reasonable personal stance looks like. Mine is simple. Keep using what keeps you connected, while pushing for cleaner operations. Read balanced reporting. A few useful primers include this status snapshot and PCWorld’s note on the daily burn-up rate. If you want to track product changes, Off-Grid Internet’s news feed on launches and network scaling, like this launch recap, keeps the pace in view.

What falling satellites tell us about risk, access, and the next ten years

Here is the paradox that sticks with me after years in patchy service areas. Starlink fixed a real problem for people left behind by old infrastructure. It delivered low-latency broadband to the edges of the map. The same scale that made that possible is what now worries scientists who track the sky. If we care about both people and planets, we have to hold two truths at once.

On the evidence side, tech outlets have tightened their language. PCWorld said plainly that at least one satellite is burning up every day. Popular Mechanics pointed to the same trend. Fast Company added that the rate is likely to climb as replacements roll in. CNET framed the sheer number in orbit and how inevitable wear leads to downfall. Daily Galaxy bundled the warnings. All of those pieces are trying to tell us something simple: growth has a bill, and it’s arriving monthly.

How should we read the warnings without panic?

By separating alarm from action. Panic is useless. Pressure plus specifics can move the needle. I like four questions when reading any new development: Does this change the number of satellites needed for coverage? Does it reduce radio emissions at the edges? Does it speed up safe disposal when a unit fails? Does it cut the chance of collision?

- Focus on ratios – megabits per satellite, not just total satellites.

- Respect quiet zones – beam shaping around observatories is a sign of care.

- Favor transparency – publish failure rates and disposal times.

| Signal from reporting | What it implies | Practical takeaway | Where to read more |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 – 2 daily reentries | Wear and tear is steady | Push for reentry mass caps | PCWorld |

| Thousands already in orbit | Density risk is real | Support debris removal pilots | CNET feature |

| Stronger interference reports | Radio hygiene needs work | Back ITU enforcement | RFI report |

| Military signals case | Rules can slip in practice | Demand live audits | Numerama article |

| V3 capacity promise | Fewer satellites for same load is possible | Ask providers for efficiency metrics | 01net preview |

Last thought here: space is not a free dump. It is a commons we all depend on, even if we never look up. If we want both connected classrooms and clear skies, then the phrase for the next decade is simple and practical: fewer, cleaner, safer.

Are one to two Starlink satellites really falling every day?

Yes. Independent analysts track reentries and tech outlets have reported the same rate. You can cross-check with PCWorld and Popular Mechanics, which cite one to two burn-ups per day as a recurring pattern. The exact count varies week to week, but the trend is upward as the constellation grows and refreshes.

Is Starlink V3 going to reduce the number of satellites needed?

It could. V3 aims for higher capacity per satellite. If operators choose to match demand with fewer, more capable units, crowding would ease. Coverage from 01net and Off-Grid Internet outlines the potential, though the final impact depends on deployment strategy.

What can users do to reduce their own footprint?

Install cleanly to avoid repeats, keep firmware current, and support policies that cap daily reentry mass and require fast disposal. If you run a business, schedule big transfers off-peak to help load. These small habits add up.

Do alternatives like Viasat or HughesNet avoid these risks?

They reduce low-orbit crowding because they sit in higher orbits, but they come with higher latency. OneWeb, Telesat, Amazon Kuiper, SES, and Iridium each balance trade-offs differently. No system is risk free, which is why smart rules matter across the board.

Why are astronomers so vocal about radio interference now?

Because they are losing time. Raised noise floors and streaked exposures ruin data. Reports from RFI and Numerama show how emissions and rule slips can hit sensitive work. Live audits and better beam control would help.